Incitement and Disavowal

An Interview with Dagmar Herzog

Welcome to the first installment of the new Wirklichkeit Books Newsletter. We will continue to inform you here about new books and events; we further hope to establish the email newsletter as an autonomous publication format including essays, comments, and recommendations by friends, collaborators, and comrades in addition to in-depth material on the publishing program. As this experiment unfolds, please reply via email to let us know what you think.

The first edition features an interview with Dagmar Herzog, whose book, The New Fascist Body, we’re publishing in September 2025. Dagmar Herzog, Distinguished Professor of History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York (CUNY), has researched extensively on the history of sexuality and religion, psychoanalysis, and the affective worlds of Nazism. It is the interrelatedness of these matters that carry her studies and help us understand the conditions of our present.

***

Jonas von Lenthe (JL): Your book Sex After Fascism. Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany (2005) was an influential contribution to debates around sexuality during and after the Third Reich. What did your study reveal and in what way did it challenge the common understanding of this topic?

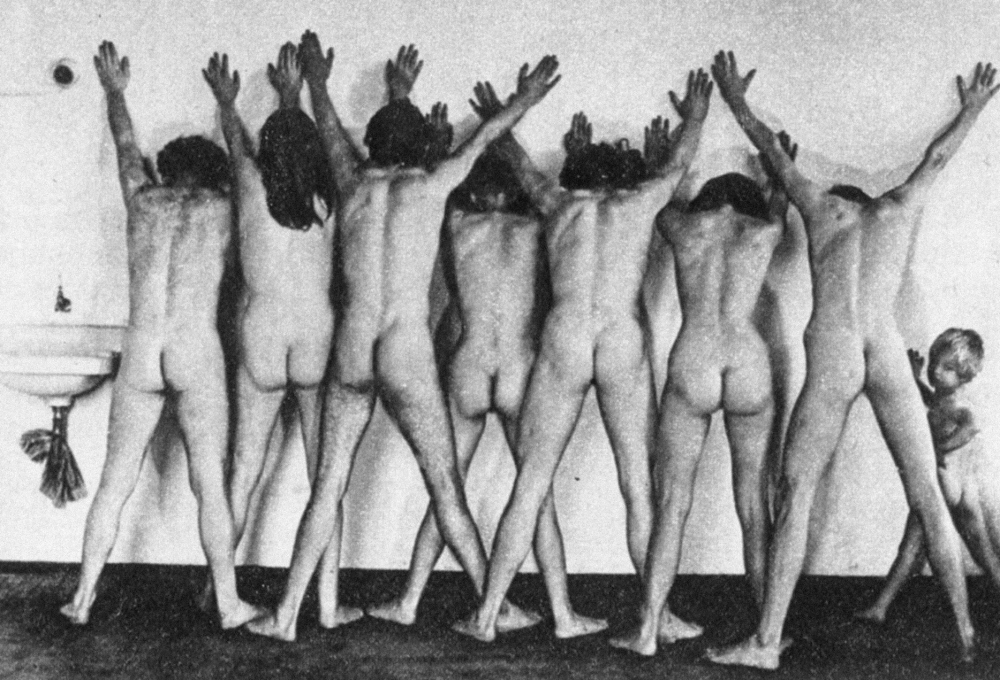

Dagmar Herzog (DH): First of all, the book made a case for the relevance of sex as a topic to be taken seriously. Sexual politics, yearnings, behaviors turn out to be far from trivial matters in twentieth-century Germany; focusing our attention on these tells us important new things about anti-Jewish feeling, the strong popular appeal of Nazism, the roles of the Christian churches, and intergenerational conflicts over post-Holocaust memory—but also about citizen-government negotiation under democratic capitalism and state socialism alike. But secondly, I guess the main provocative surprise discovery was that the Third Reich was not nearly as prudish and sexually restrictive as had long been believed—at least for nondisabled, nonhomosexual “Aryans,” that is (but that was, after all, the majority of the population). On the contrary, no prior regime in history had ever so systematically set itself the task of stimulating pre- and extramarital heterosexual desires, all while cannily denying that this was what it was doing. So I explored how exactly that combination of incitement and disavowal worked. And then thirdly, I showed how it was in battles over sexual morality that postwar Germans argued intensively with each other over the legacies of Nazism and tried to make sense of the different possible relationships between pleasure and evil. I wanted to understand how it was possible for an author in the 1960s (Arno Plack, for example—his book was a bestseller!) to assert that, “it would be wrong to hold the view that all of what happened in Auschwitz was typically German. It was typical for a society that suppresses sexuality.” That statement was historically false. But sentiments like it proved to be indispensable for advancing progressive and humane social change in postwar German society.

JL: Your most recent book, The Question of Unworthy Life: Eugenics and Germany’s Twentieth Century (2024), is a cultural history of eugenic thinking in Germany, from its emergence in the nineteenth century that led to the Nazi genocide to its continuities after 1945. In The New Fascist Body you’re connecting these two threads of your work by looking at the relation between fascism’s sexuality and its hostility to disability. How do these phenomena interact in present forms of fascism?

DH: One of the things that most strikes me about contemporary, postmodern forms of fascism—we see this now on both sides of the Atlantic—is precisely the peculiar combination of obsessive hostility to disability with what I have come to describe as sexy racism, erotically charged messaging to mobilize fear, outrage, aversion—but also excitement and thrill. We are living through the revival of a libidinally super-charged Social Darwinism. It’s uncanny to me that historical themes I had originally traced separately turn out to be so intimately intertwined, in the past and in the present. What’s happening now is that this new insistence on re-hierarchizing human worth is very deliberately being deployed in order to undermine and erode the achievements of past decades in securing broad support for the precious values of human equality, freedom, and solidarity.

JL: Psychoanalysis, its concepts as well as its history, is another of your research interests, which led you to write Cold War Freud. Psychoanalysis in an Age of Catastrophes (2017). In the book, you trace the debates around competing theories of desire, anxiety, aggression, guilt, trauma, and pleasure against the backdrop of their historical context: Nazism and the Holocaust, the sexual revolution, feminism, gay rights, and anti-colonial and anti-war activism. How does your engagement with psychoanalysis play into your other books, what role does it play in The New Fascist Body?

DH: I’ve always wanted to understand more about such knotty problems as conflicting desires, the instabilities of meanings, or the ever-mysterious relationships between psychic interiority and social context. Already in my earliest writings on the history of religion in the nineteenth century, I had to grapple with how often liberals were ill-equipped to deal with the irrational aspects of political life and the apparently potent emotional efficacy of right-wing movements. I was initially inspired to start the research for Cold War Freud because of a few individuals who had been characters in Sex after Fascism. They mixed Freud with Marx but also with Masters and Johnson, had been mentored by a combustible combination of ex-Nazis and re-émigré Jews, and were determined to recover Freud as part of the Jewish radical tradition of the first decades of the twentieth century. Their Freud was sex-positive and gay-friendly. Imagine my shock when I started reading postwar US psychoanalysis—it was authoritarian and ungenerous—but that then led to my eventual insight that there were in the Cold War era not just a handful but rather hundreds of different versions of Freud in circulation. Most recently, in The Question of Unworthy Life, I would say that my prior work on psychoanalysis was essential for helping me cope with the grotesque sadism that the archival research revealed. The crimes against the disabled were driven by both cynical careerist opportunism and absurd phantasmatic delusions. I also found helpful Freud’s concept of “afterwardsness” or “deferred effect” (Nachträglichkeit), because of the disturbingly long delay in recognizing the humanity of people with disabilities but more generally because of the recurrent strange ricochets between past and present. Those ricochets are a key feature in a little precursor book called Unlearning Eugenics, which is about reproductive justice and disability, and they’re evident in The New Fascist Body as well.

JL: The German far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is, as you show in The New Fascist Body, obsessively rejecting the inclusion of children with intellectual or emotional-behavioral impairments in mainstream classrooms—a form of anti-disability racism that seems to react to a deep-seated insecurity of not being a smart-enough nation. The AfD's anti-inclusion mobilizing could be understood as an expression of a narcissistic wound resulting from the fact that their belief in belonging to a superior “Volk” is questioned by forms of supposed imperfection within their own race. Do you see similar forms of narcissism in the political feelings in the US under Donald Trump?

DH: The present-day revival of concern with (supposed) smartness and IQ has multiple functions, one of the most important of which is the attempt to find justifications in “nature” for rising economic inequalities to legitimate austerity budgeting and cuts in social services. This is certainly happening in the US, as Trump is constantly invoking ideas of “genius” vs. “low-IQ” to flatter his voter base and to encourage contempt for all who are weak or in need of support— even as he steals massively from ordinary people to give away yet more to the ultra-rich. And the worry about the intelligence of the populace is definitely also an element in the rise of smartness talk in Germany—a phenomenon that extends, alas, well beyond the AfD. Yes, all fascisms give the designated in-group a feeling of narcissistic gain. There’s something pathetic about the master-race fantasy that doesn’t want to acknowledge that vulnerability and interdependence are parts of human life we would do well to accept. But the AfD’s strenuous resistance to inclusion in schools and insistence that children with disabilities should remain segregated—with disability thus remaining invisible to the majority society—is even more pernicious.

Dagmar Herzog is Distinguished Professor of History and the Daniel Rose Faculty Scholar at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Her many books include The Question of Unworthy Life: Eugenics and Germany's Twentieth Century (2024), Cold War Freud: Psychoanalysis in an Age of Catastrophes (2017) and Sex after Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany (2005).

ISBN 978-3-948200-20-6, 18€

Pre-order your copy here.